I am excited to be headed to Boston next month to join the Center for Advancing Teaching and Learning Through Research at Northeastern University. CATLR, led by Cigdem Talgar, was formed by Senior Vice Provost Susan Ambrose, lead author of How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. Each member of CATLR works with faculty to explore ways to enhance learning that are firmly grounded in the learning sciences. I am definitely joining a quality team … and “team” is relevant, as this appears to be a highly collaborative group.

I am excited to be headed to Boston next month to join the Center for Advancing Teaching and Learning Through Research at Northeastern University. CATLR, led by Cigdem Talgar, was formed by Senior Vice Provost Susan Ambrose, lead author of How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. Each member of CATLR works with faculty to explore ways to enhance learning that are firmly grounded in the learning sciences. I am definitely joining a quality team … and “team” is relevant, as this appears to be a highly collaborative group.

I cannot wait!

During the interview process, several members brought up the white paper that Jeff Nugent, Bud Deihl and I co-wrote back in 2009: Building from Content to Community: [Re]Thinking the Transition to Online Teaching and Learning. In the white paper, we wanted to state unequivocally that teaching online involved much more than simply posting content online. I still think that is true, even given the rise in MOOCs over the past five years. To make our case, we noted the amazing growth of open content (i.e., the content was already posted online). We then noted:

“In reviewing the literature, many suggest that the while the content and the learning outcomes are the same, the manner in which that content is delivered and the interactions with students are quite different. Ko and Rosen (2008) suggest that developing an online course starts at the same place where one develops a face-to-face course. One sets the goals for the course, describes the specific learning objectives, defines the tasks necessary to meet those objectives, and then creates applicable assignments around these tasks. The fundamentals are the same, the technique is very different. So in many ways, the design of an online course mirrors the design of a face-to-face course. Both have clear learning objectives. Assessment of learning is critical in both. Yet the fundamental practices for delivering the instruction and facilitating learner interaction are quite different.”

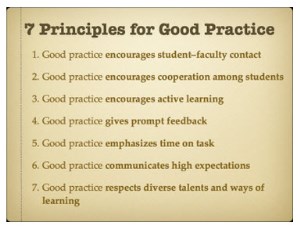

To illustrate these differences, we used a series of vignettes based on Chickering and Gamson’s Seven Principles for Good Practice for Undergraduate Education. Chickering and Gamson synthesized fifty years of research and developed the following seven principles that they viewed as core to effective teaching:

- Good Practice Encourages Student-Faculty Contact

- Good Practice Encourages Cooperation among Students

- Good Practice Encourages Active Learning

- Good Practice Gives Prompt Feedback

- Good Practice Emphasizes Time on Task

- Good Practice Communicates High Expectations

- Good Practice Respects Diverse Talents and Ways of Learning

Many others have coupled the Seven Principles with online teaching, such as in Chickering and Ehrmann’s Technology as Lever article or the recent Faculty Focus article by Dreon. As I move to CATLR, I have been thinking differently. I have been reflecting on recasting our white paper using the seven research-based principles described in Susan Ambrose’s book:

- Students’ prior knowledge can help or hinder learning.

- How students organize knowledge influences how they learn and apply what they know.

- Students’ motivation determines, directs, and sustains what they do to learn.

- To develop mastery, students must acquire component skills, practice integrating them, and know when to apply what they have learned.

- Goal-directed practice coupled with targeted feedback enhances the quality of students’ learning.

- Students’ current level of development interacts with the social, emotional, and intellectual climate of the course to impact learning.

- To become self-directed learners, students must learn to monitor and adjust their approaches to learning.

In many ways, these are “Seven Principles Two Point Oh”. 🙂 The Chickering and Gamson Seven focused on good teaching. The Ambrose Seven focus on good learning – a neat shift.

Prior Knowledge

The online environment offers the opportunity to tailor learning based on what each student brings to the course. If prior knowledge is activated, sufficient, appropriate, and accurate (not always givens), then learning can be enhanced. To do this, some form of assessment is needed to gauge and surface prior knowledge as part of the online learning process.

Knowledge Organization

This principle recognizes that novices and experts approach learning in different ways. If one approaches online learning from a constructivist and connectivist view, then strategies should be applied that help students collaboratively build connections with the concepts they are learning, teaming experts and novices. Online concept mapping exercises are a neat way to move this forward.

Motivation

Ambrose discusses the interconnections between a supportive environment, student efficacy, and the value of a learning goal – and these align with the earlier Seven Principle on High Expectations. Passion for the subject and surfacing the relevance of the learning go a long way to increasing student motivation. Empowering students to connect learning to their own passions and relevant interests applies here as well.

Mastery / Goal-Directed Practice with Feedback

In his book, The Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell suggests the “10,000-Hour Rule” – that greatness requires the investment of time and practice. In a normal semester online course, one does not have thousands of hours, but the concept of practice to develop skills is important. I coupled two of Ambrose’s principles here, because they are aligned. Goal-directed feedback coupled with timely formative and summative feedback helps mastery. It also might suggest connections between courses so that mastery grows over time across programs.

Social, Emotional, and Intellectual Climate

Every online class that I have taught has a unique personality. As the faculty teaching, I have a lot to do with the tone set for a class. The same is true for anyone teaching. Our role is be proactive about climate. Our students need safe places to try and safely fail, and then try and succeed. We need to ensure that no students feel marginalized. For me, this is a huge reason that my own social presence as the faculty member is so necessary in an online class.

Self-Directed Learners

Self-directed learners think about their own thinking. Ambrose describes a metacognitive process in which students assess tasks, evaluate their own strengths and weaknesses, plan their approaches, monitor their performance, and adjust as necessary. One of the best examples of faculty developing his students is in the blog journal of my colleague, Enoch Hale. In “Visualizing Our Intellectual Journey,” Enoch describes his efforts “…to track their intellectual journeys in clear, explicit and visual ways: then, now and into the future.”

So, I am excited to be moving to Boston and joining a high energy team! And I am excited to explore learning through a new set of lens provided by Susan’s book!

I’m going to use dimensions (maybe the spirit) of these seven principles to re-frame (although not uniquely) conversations on institutional assessment. I like how you can so concisely capture and summarize the essence of such a rich text.

Embed a picture of your new office in your next post!